I remember being scolded as a child for using the word “hate,” a word with such emotional charge my mother assured me it was not warranted … probably ever. “Stupid” had the same charge and was banished from my vocabulary. (As a teenager, I also was told not to use the word “suck” as an adjective; “that movie sucked” would get me a glare of disapproval that would wither even the most headstrong teen girl, which I happened to be.)

I will admit that my mother’s scolding sufficed only to ensure I banned these words from my vocabulary in her presence. I have used the words she added to the no-no list — hate, stupid, suck — freely and without fear of consequence for pretty much all of my adult life (along with many others). Until recently, that is, when I began ruminating on the role hatred plays in our world today, as we barrel inexorably toward the end of 2018.

Honestly, I think the presidency of Donald J. Trump has necessitated a whole lot of rumination for most of us — in the United States and abroad. No surprise, though; Trump is a paradigm-busting president, a man who thrives on chaos, a leader whose primary negotiating tool is his unwavering belief in his own charm and inevitable success.

Before it became clear that Trump would become president, I think many of us imagined that the way we mocked our political opponents was a bit of good fun, a way to blow off steam and vent our frustrations. I mean, remember the way we’d roll our eyes when George W. Bush said something particularly cringe-worthy? Jacob Weisburg at Slate began collecting Bushisms in October 1999, when W. was just beginning his run for president. There were page-a-day calendars of Bushisms during the Bush 43 presidency, and liberal America embraced the mockery of a less-than-brilliant president as it dared hope for a better day.

Neil Postman’s cautionary book Amusing Ourselves to Death, published in 1985 (!!!!), felt immeasurably prescient when I read it for the first time in the late 1990s. Rereading it a couple of months ago left me reeling, honestly. Postman argues that television was creating a country of citizens unprepared to rise to the task democracy demands of them. He wrote: “Americans are the best entertained and quite likely the least well-informed people in the Western world” (p. 106).

And that was in 1985.

It hasn’t gotten better in the thirty-something years since. Indeed, the Internet (and especially social media) have ushered in an era in which near-constant amusement is possible. As for that notion that technology was creating citizens ill-prepared for the demands of democracy, Postman predicted that entertainment technologies were “creating a species of information that might be properly called disinformation … misleading information that creates the illusion of knowing something but which in fact leads one away from learning” (p. 107).

Add in a dabble of tribal psychology (I tip my hat here to Jonathan Haidt’s book, The Righteous Mind, a book that captures more wisdom than I can fathom), and we have a real crisis on our hands. Namely, as Haidt summarizes in his TED Talk (which I’ve now seen at least 200 times, no joke):

Our righteous minds were designed by evolution to unite us into teams, to divide us against other teams, and then to blind us to the truth.

“The Moral Roots of Liberals and Conservatives,” TED2008.

There are a number of threads here I’m trying to weave together into what is, I’m afraid, a rather bleak tapestry: mocking less-than-brilliant presidents, media environments that actively work against democracy’s requirements, and a tribal psychology that prevents us from seeing the truth once we’ve identified with a particular ‘team,’ in this case a political party or orientation.

There are good reasons to oppose those who hold different political views. If you identify as left-leaning or liberal, you might draw a sketch of the right as repressive, xenophobic, or authoritarian. Those who lean right or identify as conservative might similarly describe those on the left as the real agents of chaos, disregarding rules and national sovereignty and, at their worst, inviting murder and mayhem.

Why on Earth would you ever befriend someone who wants to destroy the world you live in (or want to live in)? Why would you give someone the benefit of the doubt when they are actively working to prevent you from living your Very Best Life?

The tribal impulses kick in, the entertainment we mistakenly call “news” distracts us from the truth, we mock and criticize and allow ourselves to feel hatred toward those on the other side of the political aisle.

This progression makes perfect sense. It feels so good to be so damned certain we’re right. It feels so reassuring to be certain your conception of the world will make everything better.

Yet, it’s exactly that feeling — the thing that feels so damned good — that will bring about our downfall. I’ve never been more certain of anything. (And yes, I recognize the irony in those two statements. I do.)

Ultimately, the opposite of hate is the beautiful and powerful reality of how we are all fundamentally linked and equal as human beings. The opposite of hate is connection.

The Opposite of Hate, by Sally Kohn, p. 228

Let me turn to Sally Kohn, a progressive commentator (who, it turns out, was at GWU at the same time as me — go figure!) who has recently written a book called The Opposite of Hate: A Field Guide to Repairing Our Humanity. Sally has no reason to feel warm and fuzzy about the world; she brags early in her book about how “I have some of the worst trolls” on Twitter — a compliment (?) someone else gave her on Twitter.

Kohn’s premise in her book is that hatred, no matter how good it might feel in the moment, is ultimately not helping us … not at all. She writes:

“The opposite of hate also isn’t some mushy middle zone of dispassionate centrism. You can still have strongly held beliefs, beliefs that are in strong opposition to the beliefs of other people, and still treat those others with civility and respect. Ultimately, the opposite of hate is the beautiful and powerful reality of how we are all fundamentally linked and equal as human beings. The opposite of hate is connection” (p. 228, emphasis added).

Hate frays our connections to one another. When we lecture someone about how they should behave differently, believe differently, feel differently, we are creating uncross-able barriers that ultimately serve to lessen our humanity as it lessens theirs. I’ll come back, once more, to something Bryan Stevenson writes in Just Mercy:

“We are all implicated when we allow other people to be mistreated. An absence of compassion can corrupt the decency of a community, a state, a nation. Fear and anger can make us vindictive and abusive, unjust and unfair, until we all suffer from the absence of mercy and we condemn ourselves as much as we victimize others” (p. 18, emphasis added).

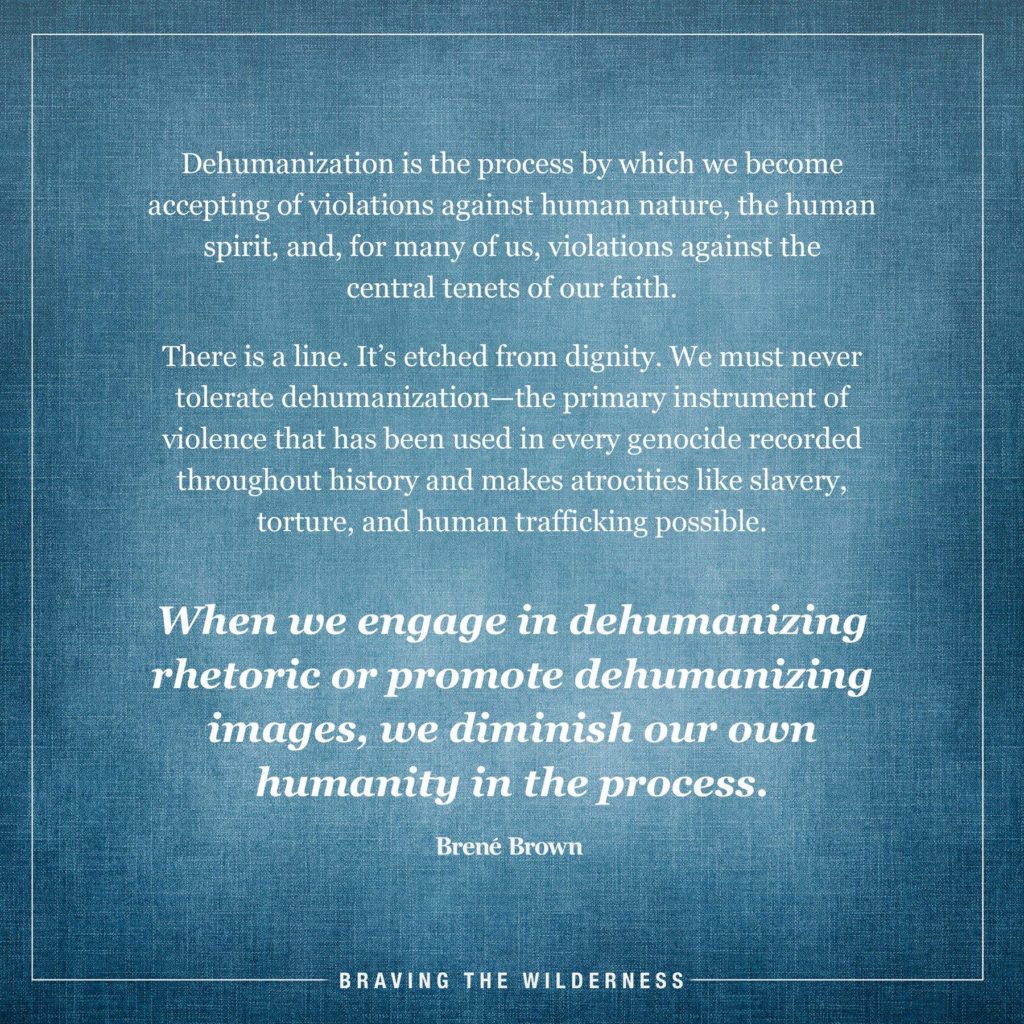

This is something Mama Brené (Brown) talks about, too, particularly in her book Braving the Wilderness:

I recognize that this blog post is much longer than what I normally write, and it’s chock full of nuggets that might send you to Amazon to stock up on some reading (which would be honestly an ideal outcome, IMO). But this is important stuff.

The second you start to use your voice to preach your message of righteousness, you’ve fallen down into a rabbit hole echo chamber that actually does your cause more harm than good.

If we want to make this world a better place — and I genuinely believe that, at our hearts, we all want that, we are only going to do it by recognizing the good in one another.

That doesn’t mean you need to embrace ideologies with which you vehemently disagree. Instead, it means that you need to befriend those who have those ideologies. Embrace those who disagree with you, even if only metaphorically. Talk to them like the people they are.

As Bryan Stevenson’s grandma told him, and as Mama Brené tells us, it’s very hard to hate up close. We must embrace what Antonin Scalia said on 60 Minutes once: “I attack ideas; I don’t attack people. And some very good people have some very bad ideas.” (Watch that interview here; he makes this comment at 6:45.)

If Antonin Scalia and Ruth Bader Ginsburg can be the best of friends, if Larry Flynt (“peddler of smut”) and Jerry Falwell can become friends, I don’t believe we’re encountering insurmountable differences, not if we are willing to recognize what we have in common as humans on this hunk of rock in 2018.

This is my Christmas wish: A little more compassion. A little more benefit of the doubt. And a whole, whole lot less hate.

I love this post and I embrace it, but because I’m a white cis-woman. I think my role is to try to be kind and understanding to a point. My issue is that sometimes I see this concept of friendship despite differences applied to POC or LGBTQIA+ persons. I think it is my job as a cis white woman to do that emotional labor, but certainly not the job of POC or queer people to ever feel like they need to reach across the aisle in friendship. I have so many friends who are exhausted from constantly trying to rise above and maintain a loving heart. So yes, I agree whole-heartedly AND I think it is important that we not put that pressure on historically oppressed people.

Amanda, I completely agree that it’s unfair to place the burden of compassion on those who are the victims of oppression. That said, I’m aware of the need to think through what our goals are. As Irene Lyon points out, if you’re under active, immediate threat to your survival, then it’s unreasonable to think you’re going to extend a compassionate hand to those who are threatening your life. But if those who fall under the mantle of “social justice warrior” (as I do myself) are only interested in pointing out where other people are mistaken, nothing will get better … indeed, things will only get worse. I take to heart Jonathan Haidt’s point that nobody thinks they are wrong. If we want to change people, we must first understand them and then make an argument that resonates with them. This isn’t necessarily pleasant work, but it’s what I believe is absolutely necessary if we want to stop the downward spiral we see today. And, as someone who has pretty strong social justice inclinations, I can tell you that this practice (and it’s DEFINITELY a practice!) gets easier and it definitely makes my overall stress levels stay in reasonable zones more often. That doesn’t mean I excuse oppressive acts. If Bryan Stevenson can reserve compassion for those who prosecute (beyond legal limits, often) innocent black men, I think there’s hope for us all. <3